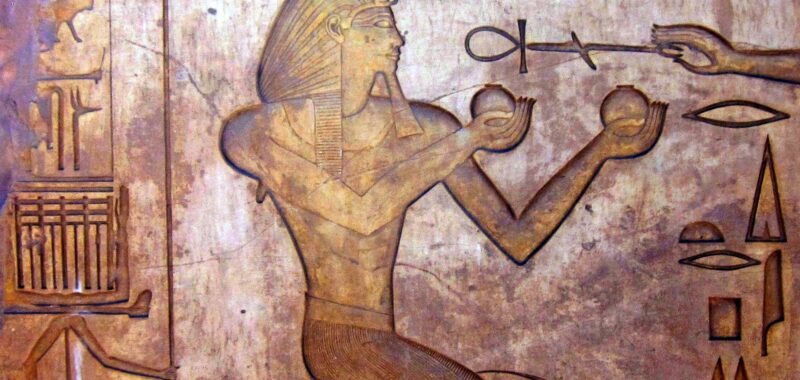

Compared to his royal relatives, King Thutmose II doesn’t get much attention. Depending on the documentation, the monarch only ruled over ancient Egypt for 13 years (1493-1479 BCE) at most, and possibly as little as three (1482-1479 BCE). Egyptologists tend to focus more on his father, Thutmose III; half-sister and wife, Queen Hatshepsut; and son, Thutmose II.

But that doesn’t make the discovery of his final resting place any less important. On February 18, the Egyptian government announced that an international team of archeologists have finally confirmed the tomb’s location—making it the first and most significant royal find since the identification of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922.

The story of recovering Thutmose II’s remains dates back to the 19th century, when researchers found the king’s mummified body at what is known as the Deir el-Bahari Cachette. But the site clearly wasn’t the mummy’s original location, leading experts to wonder about the whereabouts of Thutmose II’s original tomb for well over a century.

In 2022, experts unearthed a site a few miles west of Luxor and the Valley of Kings, which they designated Tomb No. C4. Given its relative simplicity and location near Queen Hatshepsut’s grave, archeologists initially theorized No. C4 contained one of King Thutmose III’s wives. The room and its features had been heavily damaged by flooding, making it difficult to understand its overall context. Further excavation also yielded the discovery of a second, smaller corridor thought to have been a robber’s tunnel.

“Despite its significance, the tomb was found in poor condition, flooded in antiquity shortly after the king’s death. Water damage caused severe deterioration, leading to the loss of many original contents, which are believed to have been relocated during ancient times,” Mohamed Abdel Badei, head of the Ancient Egyptian Antiquities Sector and project co-lead, said in a statement.

But despite the flooding, the vault wasn’t devoid of artifacts—and what archeologists found actually confirmed the tomb’s original inhabitant. According to Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, alabaster vase fragments spelled out not only Thutmose II’s name, but his final status as a “deceased king.” Other finds included plaster painted blue and decorated with yellow stars, along with portions of the Book of Amduat, a key religious text used during Egyptian royalty burial rituals. Researchers could also confirm that Queen Hatshepsut—one of only two queens known to rule over ancient Egypt—oversaw the burial of her husband and half-sibling.

Further analysis appears to solve not only the reason for the removal of Thutmose II’s mummy, but the mystery corridor’s purpose. Researchers now believe it wasn’t robbers who built the tunnel, but royal attendants who rescued the king’s remains from the flooded chamber. As excavation work continues, archeologists hope to learn even more answers about life during Thutmose II’s brief reign, as well as details about the rescue effort to recover his body from the flooded tomb.