To keep warm during the most recent ice age, early humans needed protective clothing. What these garments looked like and just how they were put together has remained an archeological mystery. Now, a team in Wyoming found that Paleolithic North Americans likely made needles using the bones of foxes, hares, rabbits, bobcats, mountain lions, lynx, and even the now-extinct American cheetah. Archaeologists also recently found the oldest known bead in the Americas at this site–which was made from the bone of a hare. The bone needles are described in a study published November 27 in the journal PLOS ONE.

The bone needles were uncovered at a Wyoming archaeological site that sheds light on some of the early inhabitants of North America called La Prele. Previously, archaeologists uncovered evidence that humans killed or scavenged a Columbian mammoth about 13,000 years ago. La Prele was occupied during the final years of the last Ice Age, when it was likely around nine to 11 degrees colder in Wyoming.

“Our team on this study largely adheres to the notion that the first Americans arrived south of the North American continental ice sheets sometime around 13,000 years ago and are associated with the Clovis cultural complex,” Spencer Pelton, a study co-author and Wyoming State Archaeologist, tells Popular Science. “Given its age, the occupants at La Prele could have been the grandchildren or great grandchildren of the first Americans.”

According to Pelton, bone needles are common during this period in the North American archaeological record because sewing complex weather garments for freezing weather was a necessity in response to the cold climate shift brought on by the last ice age. Early humans at northern latitudes likely created tailored garments with closely stitched seams that provide a better barrier against the elements. There has been little direct evidence of such garments, but bone needles and the bones of the fur-bearing animals used to make pelts provide some indirect evidence of this early tailoring.

“Bone needles are extremely small, but when they pop up on the screen they’re pretty unmistakable once you get an eye for them,” says Pelton.

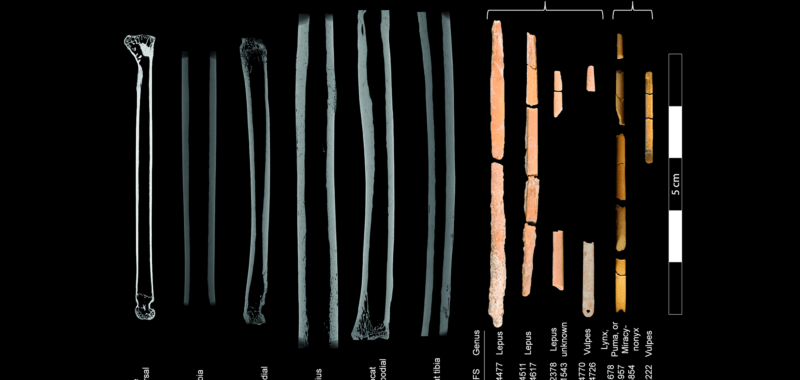

To identify the bone needles and bead, the team on this study used zooarchaeology by mass spectrometry (ZooMS), micro-CT scanning, and extracted collagen from the 32 bone needle fragments. They compared the bone needle peptides–short chains of amino acids–with peptides from animals known to have lived in the area during the Early Paleondian Period in North America (about 13,500 and 12,000 years ago).

[Related: Ice Age humans may have used pikes to hunt mammoths.]

They found that the bones from several animals were probably used to make these needles: red foxes, bobcats, mountain lions, lynx, the American cheetah, hares, and rabbits were used to make needles at the LaPrele site. These animals were surprising to the team, since Early Paleoindian sites on the Great Plains are typically dominated by the bones of large animals like bison and mammoths. Remains of fauna including red fox, rabbits, and cats indicate that humans were likely running trap lines to catch the smaller animals.

“[This] really altered our perception of Early Paleoindians as solely large game hunters,” says Pelton.

While there are currently no examples of preserved Paleolithic clothing, the team believes that these bone needles are some of the best evidence yet of what clothing may have looked like at this time and how similar it is to clothing worn by Indigenous peoples living today.

“They were complex garments fringed with the furs of red fox, hare, and cat, some of which with feet still attached as is common among modern trappers,” says Pelton. “They were likely comparable to similar garments worn by the Inuit, able to withstand the cold and windy conditions of Wyoming’s last Ice Age.”