Some areas of modern Europe were pretty populated during the Stone Age. Archeological evidence shows that settlements in present day Ukraine may have had 10,000 to 15,000 people living there. Now, a new bioarcheological analysis was conducted on the remains of some of these Neolithic Europeans from an archaeological site near Kosenivka, Ukraine. The people who lived here over 5,600 years ago ate mostly plants, farmed, and some may have perished in an accidental fire. The first-of-their-kind findings are detailed in a study published December 11 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE.

The inhabitants of this settlement are associated with the Cucuteni-Trypilla culture. This group is primarily known for their pottery and lived across what is now Eastern Europe from roughly 5500 to 2750 BCE. Archeologists designate some of their settlements “mega-sites,” that were home to up to 15,000 people.

“The Trypilla societies were the first successful farmers in this area,” Katharina Fuchs, a study co-author and biological anthropologist and archaeologist from Kiel University in Germany, tells Popular Science. “They knew how to cultivate the environment, grow cereals and legumes, exploit the woodlands and breed their livestock. They are also known for their beautiful pottery, which they produced in a really high amount. Additionally, the settlement structures suggest early, quite complex sociopolitical systems to organize life in such megasites.”

Despite the numerous artifacts the Trypillia left behind, archeologists have not found many human remains. Without these skeletal records, many facets of their lives are still undiscovered, including how they treated their dead.

![Archaeological context of Kosenivka. A: Map showing the location of the settlement of Kosenivka and the Chalcolithic sites referred to in the text. B: Photo showing the location of house 6 within the landscape. C: Photo showing house 6 being excavated, in 2004. CREDIT: Map: R. Hofmann. Photos: republished from Kruts et al. [22] under a CC BY license with permission from V. Chabanyuk, original copyright 2005). Fuchs et al., 2024, PLOS ONE.](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/ukraine-dig-map.png?strip=all&quality=85)

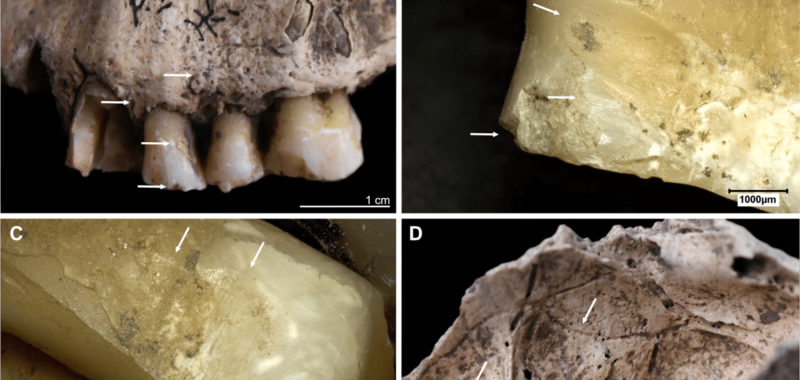

In this new study, Fuchs and an interdisciplinary team of researchers studied a settlement site near Kosenivka, Ukraine where 50 human bone and tooth fragments have been recovered. The bones were found among the remains of a house and appear to belong to at least seven individuals of mixed ages and gender who may have been inhabitants of the house. Four of the individuals also have heavily charred remains and the team investigated the potential causes of these burns.

The burnt pieces of bone were primarily found in the center of the house. Previous studies of these bones proposed that the inhabitants perished in a house fire. While closely studying the pieces under a microscope, the team concluded that the burning likely occurred quickly after their deaths and was accidental. The researchers believe that some individuals might have died of carbon monoxide poisoning, even if they managed to get out of the house.

[ Related: Europe’s oldest human-made megastructure may be at the bottom of the Baltic Sea. ]

According to additional radiocarbon dating, one of the individuals about 100 years later and the team could not connect this person’s death to the fire. Two other individuals had unhealed cranial injuries, which raises some questions about if violence played a role in their deaths.

The chemical analysis of bone and tooth fragments also revealed more on how they may have lived. The teeth found at the site have wear marks that indicate chewing on grains and other plant fibers to clean them.

“These Trypillian societies relied mainly on a plant-based diet and keeping cattle was not for meat production, but for milk production and to fertilise the fields,” says Fuchs.

According to Fuchs, parts of this site were first excavated decades ago and have not been “destroyed directly by military offensives” in Ukraine. However, the work of archaeologists and other experts who work on cultural heritage sites like Kosenivka has heavily been impacted by the war, with damage reported to several buildings, including museums and churches. Since the invasion began in 2022, Kiel University archaeologists have committed to strengthening collaborations with Ukrainian colleagues in the face of the crisis and this study is part of that effort.

“Exploring our deep history has never been as important as it is today–our behaviour in and with the environment and, of course, with each other,” says Fuchs. “Bones are not an abstract thing, but the biological and chemical archive of a human life. Even the smallest bone fragments can help us to see ourselves in the mirror of the past and thus develop a different view of the present, but also of the future.”